Catching AI with its pants down: Some Musings About AI

| We will strip the mighty, massively hyped, highly dignified AI of its cloths, and bring its innermost details down to earth! |

- Objective

- Motivation

- Artificial General Intelligence: The Holy Grail of AI

- Artificial Narrow Intelligence

- Machine learning

- Estimators

Objective

The goal of this writeup is to present modern artificial intelligence (AI), which is largely powered by deep neural networks, in a highly accessible form. I will walk you through building a deep neural network from scratch without reliance on any machine learning libraries and we will use our network to tackle real public research datasets.

To keep this very accessible, all the mathematics will be simplified to a level that anyone with a high-school or first-year-university level of math knowledge and that can code (especially if Python) should be able to follow. Together we will strip the mighty, massively hyped, highly dignified AI of its cloths, and bring its innermost details down to earth. When I say AI here, I’m being a little silly with buzzspeak and actually mean deep neural networks.

However, all the code presented in this blog series can be found at this GitHub repo, and includes code for artificial neuron and deep neural networks from scratch. Even the codes for the latter articles are already available there.

This writeup aims to be very detailed, simple and granular, such that by the end, you hopefully should have enough knowledge to investigate and code more advanced architectures from scratch if you chose to do so. You should expect a lot of math, but don’t let that scare you away, as I’ll tried my best to explain things as simply as possible.

The original plan was to explain everything in one giant article, but that quickly proved unwieldy. So, I decided to break things up into multiple articles. This first article is basically some casual ramblings about AI with a brief overview of machine learning, and subsequent articles focus on introducing an artificial neuron, the derivation of the equations needed to build one from scratch and the code implementation of those equations, and then repeat all that for a network of artificial neurons (a.k.a. neural networks).

| Parts | The complete index for Catching AI with its pants down |

|---|---|

| Pant 1 | Some Musings About AI |

| Pant 2 | Understand an Artificial Neuron from Scratch |

| Pant 3 | Optimize an Artificial Neuron from Scratch |

| Pant 4 | Implement an Artificial Neuron from Scratch |

| Pant 5 | Understand a Neural Network from Scratch |

| Pant 6 | Optimize a Neural Network from Scratch |

| Pant 7 | Implement a Neural Network from Scratch |

| Pant 8 | Demonstration of the Models in Action |

Motivation

My feeling is if you want to understand a really complicated device like a brain, you should build one. I mean, you can look at cars, and you could think you could understand cars. When you try to build a car, you suddenly discover then there’s this stuff that has to go under the hood, otherwise it doesn’t work.

The entirety of the above paragraph is one of my favourite quotes by Geoffrey Hinton, one of the three Godfathers of Deep Learning. I don’t think we need any further motivation for why we should peek under the hood to see precisely what’s really going on in a deep learning AI system.

Tearing apart whatever is under the hood has been my canon for my machine learning journey, so it was natural that I would build a deep neural network from scratch especially after I couldn’t find any such complete implementation online (as of 2018 to early 2019). Some of my colleagues thought it would be good if I put together some explanation of what I did, and so the idea for this writeup was born.

Artificial General Intelligence: The Holy Grail of AI

Artificial intelligence (AI) is the intelligence, or the impression thereof, exhibited by things made by we humans. The kind of intelligence we have is natural intelligence. A lot of things can fall under the umbrella of AI because the definition is vague. Everything from the computer player of Chess Titans on Windows 7 to Tesla’s autopilot is called AI.

Artificial general intelligence (AGI) is the machine intelligence that can handle anything a human can. You can think of the T-800 from The Terminator or Sonny from I, Robot (although in my opinion, the movie’s view of AI, at least with regards to Sonny, aligns more with symbolic, rule-based AI instead of machine learning). Such AI system is also referred to as strong AI.

AGI would be able to solve problems that were not explicitly specified in its design phase. There is no AGI system in existence today, nor is there any research group that is known to be anywhere close to deploying one. In fact, there is not even a semblance of consensus on when AGI could become reality.

Tech author Martin Ford, for his 2018 book Architects of Intelligence, surveyed 23 leading AI figures about when there would be a 50 percent chance of AGI being built. Those surveyed included DeepMind CEO Demis Hassabis, Head of Google AI Jeff Dean, and Geoffrey Hinton (one of the three Godfathers of Deep Learning).

Of the 23 surveyed, 16 answered anonymously, and 2 answered with their names. The most immediate estimate of 2029 came from Google director of engineering Ray Kurzweil and the most distant estimate of 2200 came from Rod Brooks (the former director of MIT’s AI lab and co-founder of iRobot). The average estimate was 2099.

There are many other surveys out there that give results in the 2030s and 2040s. I feel this is because people have a tendency to want the technologies that they are hopeful about to become reality in their lifetimes, so they tend to guess 20 to 30 years from the present, because that’s long enough time for a lot of progress to be made in any field and short enough to fit within their lifetime.

For instance, I too get that gut feeling that space propulsions that can reach low-end relativistic speeds should be just 20 to 40 years away; how else will the Breakthrough Starshot (founded by Zuckerberg, Milner and the late Hawking) get a spacecraft to Proxima Centauri b. Same for fault-tolerant quantum computers, fusion power with gain factor far greater than 1, etc. They are all just 20 to 40 years away, because these are all things I really want to see happen.

Also, it seems that AI entrepreneurs tend to be much more optimistic about how close we are to AGI than AI researchers are. Someone should do a bigger survey for that, ha!

Artificial Narrow Intelligence

The type of AI we interact with today and hear of nonstop in the media is artificial narrow intelligence (ANI), also known as weak AI. It differs from AGI in that the AI is designed to deal with a specific task or a specific group of closely related tasks. Some popular examples are AlphaGo, Google Assistant, Alexa, etc.

A lot of the hype that has sprung up around ANI in the last decade was driven by the progress made with applying deep neural networks (a.k.a. deep learning) to supervised learning tasks (we will talk more about these below) and more recently to reinforcement learning tasks.

A supervised learning task is one were the mathematical model (what we would call the AI if we’re still doing buzzspeak) is trained to associate inputs with their correct outputs, so that it can later produce a correct output when fed an input it never saw during training. An example is when Google Lens recognizes the kind of shoe you are pointing the camera at, or when IBM Watson transcribes your vocal speech to text. Google Lens can recognize objects in images because the neural network powering it has been trained with images where the objects in them have been correctly labelled, so that when it later sees a new image it has never seen before, it can still recognize patterns that it already learned during training.

In reinforcement learning, you have an agent that tries to maximize future cumulative reward by exploring and exploiting the environment. That’s what DeepMind’s AlphaGo is in a nutshell. It takes in the current board configuration as input data and spits out the next move to play that will maximize the chances of winning the match.

The important point is that deep neural networks have been a key transformative force in the development of powerful ANI solutions in recent times.

Machine learning

The rise of the deep learning hype has been a huge boon for its parent field of machine learning. Machine learning is simply the study of building computers systems that can “learn” from examples (i.e. data). The reason for the quotes around “learn” is that the term is just a machine learning lingo for mathematical optimization (and we will talk more about this later). We will also use the term “training” a lot, and it also refers to the same mathematical optimization.

In machine learning, you have a model that takes in data and spits out something relevant to that data. For the task of labelling images of cats and dogs (see image above), a model will receive images as input data and then it will output the correct labels for those images. This is a task that is trivial for humans, but was practically impossible for computer programs to consistently perform well at until convolutional neural networks came along. This is because it is extremely laborious to manually write programs to identify all the patterns needed to identify the primary object in the image, which leaves machine learning as a more feasible route.

Supervised vs. Unsupervised Learning

The two main broad categories of machine learning are supervised learning and unsupervised learning. The main distinction between the two is that in the former the program is provided with a target variable (or labelled data in the in the context of classification) and in the latter, no variable is designated as the target variable.

But don’t let the “supervision” in the name fool you, because, as of 2020, working on real-world unsupervised tasks requires more “supervision” (in the form of domain-specific tweaks) than supervised tasks (which can still benefit from domain-specific tweaks). But there is a general sense of expectation that unsupervised learning will start rivalling the success of supervised learning in terms of practical effectiveness (and also hype) within the next few years.

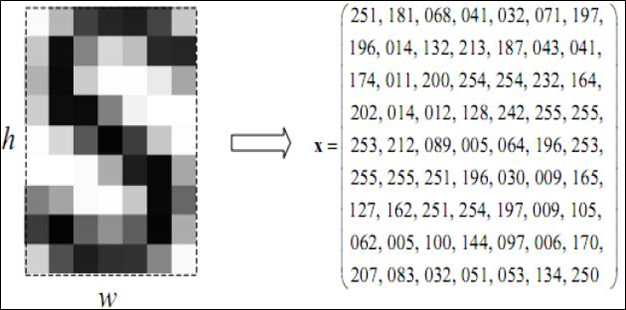

In supervised learning, the dataset will have two part. One is the target variable (\(y\)) that holds the values to be predicted, and the other is the rest of the data (\(x\)), which are also called the input variables, independent variables, predictors, or features. The target variable \(y\) is also called the output variable, response, or dependent variable, ground truth. It’s quite useful to be able to recognize all these alternative names.

For instance, in an image classification task, the pixels of the image is the input variables and the label for the image is the target.

A datapoint also goes by many names in the ML community. Names like “example”, “instance”, “record”, “observation”, etc., are all monikers for “datapoint”. I may use examples and records as alternatives to datapoint every now and then in this blog series, but I will mostly stick to using datapoint.

Supervised learning: Regression vs Classification

The two broad categories of supervised learning are classification and regression. In classification, the target variable has discrete values, e.g. cat and dog labels. There can’t be a value between cat and dog. It’s either a cat or a dog. Other examples would be a variable that holds labels for whether an email is spam or not spam, or labels for hair color, etc.

In regression, the target variable has continuous values, e.g. account balances. It could be -\$50 or \$20 or some number in between that. It could be floating point number like \$188.5555, or really large positive or negative number.

Reinforcement learning

Another subset of machine learning that some consider a category of its own alongside supervised learning and unsupervised learning is reinforcement learning. It’s about building programs that take actions that affect an environment in such a way that the cumulative future reward is maximized; in other words, programs that love to win!

You may run into other sources that consider it a hybrid of both supervised and unsupervised learning (i.e. semi-supervised learning). This is debatable because there is no label or correction involved in the training process, but there is a reward system that guides the learning process.

Also be careful, because reinforcement learning is not a definitive name for the hybrids of the two. There are other subsets of machine learning that are truer hybrids of supervised and unsupervised learning but do not fall under reinforcement learning. For instance, generative adversarial neural networks (the family of machine learning models behind the deepfake technology).

Deep Learning

Deep learning is simply machine learning that focuses on deep neural networks, which is a network of artificial neurons stacked into several layers. Deep neural networks can be used for supervised, unsupervised and reinforcement learning. As such, deep learning can intersect with all three major categories of machine learning.

However, much of the advances we’ve seen with deep learning in the last two decades has been for supervised learning and reinforcement learning. But there is a lot of ongoing work to make deep learning work great for unsupervised learning as it has for the other two.

Estimators

When you see an apple, you are able to recognize that the fruit is an apple. When the accelerator (gas pedal) of a car is pressed down, the velocity of the car changes. When you see a ticktacktoe board where the game is ongoing, a decision on what is the best next move emerges.

All of these have one thing in common: there is a process that takes an input and spits out an output. The visuals of an apple is the input and the recognition of the name is the output. Pressing down of the accelerator is an input and the rate of change of velocity is the output.

All of these processes can be thought of as functions. A function is the mapping of a set of inputs to a set of outputs in such a way that no input maps to more than one output. Almost any process can be thought of as a function. The hard part is fully characterizing the function that underlies the said process.

An estimator is a function that tries to estimate the behavior of another function whose details are not fully unknown.

An estimator is the core component of a supervised machine learning system. It goes by many other names including being simply called the model, approximator, hypothesis function, learner, etc. But note that some of these other names, like model and learner, can also refer to more than just the estimator. For example, model can refer to an entire software system instead of just the mathematical model.

Let’s say there is a function (\(f_{actual}\)) that takes \(x\) as an input and spits out \(y\), then an estimator (\(f_{estim}\)) will take in the same \(x\) as its input and will spit out \(\hat{y}\) as an output. This \(\hat{y}\) will be expected to be approximately same as \(y\).

\[y=f_{actual}\left(x\right)\] \[\hat{y}=f_{estim}\left(x\right)\]Because we expect that there may be a difference between \(y\) and \(\hat{y}\) (preferrably a very small difference), we introduce an error term to capture that difference:

\[\varepsilon=y-\hat{y}\]Therefore, we can then see that:

\[y=\hat{y}+\varepsilon\]Or written as:

\[y=f_{actual}\left(x\right)=f_{estim}\left(x\right)+\varepsilon\]We notice that if we can minimize \(\varepsilon\) down to a really small value, then we can have an estimator that behaves like the real function that we are trying to estimate:

\[y \approx \hat{y}=f_{estim}\left(x\right)\]We will revisit the error when we go over the loss function for an artificial neuron.

If you’ve heard of naïve Bayes, logistic regression, linear regression, or k-nearest neighbours, then you’ve heard of other examples of machine learning estimators. But those are not the focus of this blog series (although logistic regression is kind of), nor do you need to know how those work to follow along in this series.

comments powered by Disqus